The orchestra is continuing to build on a three-decades history of anti-racism and anti-sexism. At least one-third of its musicians, staff and board are people of color, making it a notable outlier in the orchestral world.

Category: News & Press Releases

Chicago Sun-Times | Chicago Sinfonietta kicks off 33rd season with continued focus on diversity

Six artists of color make their mark in classical music | Chicago Sun-Times, August 2020

Kyle MacMillan of the Chicago Sun-Times spoke with Chicago Sinfonietta Principal Violist Marlea Simpson for a feature on the future of classical music.

“According one report, the share of African American and Latino musicians in American orchestras stood at just 2.5 percent in 2014.

Success for Marlea Simpson will be when the entire field functions like the Chicago Sinfonietta, where the African American musician has served as principal violist since 2014. The ensemble is an unusual outlier in the orchestral realm, because at least one third of its musicians, staff and board are people of color.

“I get to experience classical music in the way I feel it should be experienced,” she said.”

The Southside Friends of Chicago Sinfonietta present “Summer Magic” | August 2020

The Southside Friends of Chicago Sinfonietta presented Summer Magic: A Virtual Brunch on August 4, 2020 to help raise critical funds to support musician operations in the wake of the devastating impact of COVID-19.

The program was a success, providing much needed support for our musicians through general operating expenses with lively performances that celebrated the future of Chicago Sinfonietta.

“Summer Magic: A Virtual Brunch kicked off at 11 a.m. Saturday morning. Many of those speaking on behalf of the Chicago Sinfonietta held a glass flute filled with a sparkling beverage, and by the end of the online event I expect that many of those listening raised their own glasses, or perhaps mugs of tea or coffee, in honor of the group’s achievements and the enjoyable performances from the musicians.” —Hyde Park Herald

Missed the live event? Watch online now.

Chicago Sinfonietta Confronts Racial Bias In Classical Music | Newcity Music, July 2020

Seth Boustead of New City Music speaks with Project Inclusion Director Danielle Taylor for an insider perspective on Chicago Sinfonietta’s groundbreaking fellowship and education program.

“What does it mean to make art now? When survival is the primary thing on our mind, and then also to do so under circumstances where you can’t make art with people, like in the same room with people, which I think for Black people, culturally has been so, so important in surviving in this country. Being together and making music, from churches to jazz. Being deprived of that at this moment is yet another piece that feels so broken.”

Violinist, violist, writer and thinker Danielle Taylor is not talking about survival figuratively or only in relation to the coronavirus. In a country that routinely murders its citizens for being Black, and too often lets perpetrators get away with it, she is talking about actual survival.

I had contacted Taylor about her role as director of Project Inclusion at the Chicago Sinfonietta to talk about the initiative’s extraordinary work. I had a conundrum on my hands: I had agreed to write the classical music article for Newcity for July but there are no performances to write about and, given our current climate, writing about how classical music groups are reaching audiences virtually felt tone deaf.

As in the wake of the MeToo movement, classical music is having to confront a legacy most organizations would prefer not to talk about—in this case, a long legacy of racial exclusion in nearly every area, from the stage to key administrative and management positions.

It’s this legacy that Project Inclusion hopes to change. “This fellowship exists to make up for the lack of opportunities and all the years that come before,” Taylor says. “Those opportunities look like private lessons but also the privilege of choice, because what money can provide is the choice of saying, okay, this teacher doesn’t work for my child anymore. So we’re going to move to a different teacher who can prepare them at a higher level.

“And there are so many people who come up through very important nonprofit schools, yes; but that does not compare to intensive one-hour lessons where you can choose who’s going to take you to the next level. Then there are festivals which are extremely expensive, and there are people who can’t afford the application fee, let alone a plane ticket to get there.

“We can’t talk about race without also talking about economics, without talking about who has the accumulated wealth in the country. And it has not been Black people and people of color and that leads to exclusion. When there are people not feeling welcomed or encouraged or supported by their institutions and teachers, ultimately that can lead to dropping out, to deciding to take a different career path.

“By the time you get to the people who are actually in the field and have jobs, that’s such a small number of the people who would have worked passionately with all their might to get there.”

Project Inclusion currently has fellowships for string players and conductors, and are adding a composition fellowship this year. The training is intensive and hands-on. The fellows take private lessons and master classes, but perform with the Chicago Sinfonietta as well, an incredible opportunity. They also practice mock auditions and media interviews and master all aspects of being a successful classical musician, on and off stage.

“There’s also the time and the space to talk openly about the challenges that our fellows face navigating the field,” Taylor says, “because it can’t be divorced from race and gender and all of the often-negative ways that we’re perceived. Allowing that space to have those conversations is also important. The power of Project Inclusion comes from building a strong community with all of the fellows and instead of seeing each other as competitors, they see each other as family.”

But Project Inclusion is only one project at one institution. Reaching the goal of changing the face of classical music, it’s going to take all of us. If you use email, you’ve probably been barraged with messages from arts organizations saying they “stand in solidarity” with the protest movements. These are noble sentiments and I don’t doubt the sincerity of organizations sending them out. But you don’t have to look far to see that by not acknowledging the history of exclusion and the pain that it has caused, these messages often do more harm than good. Just by being part of the fabric of a racist society, most institutions are complicit.

“Every single one of these institutions absolutely has enacted harm,” Taylor says. “It’s part of their organizational structure because your organization is not an organization. It is a building filled with people that make decisions, and those people have values and prejudices and all of that. So to me, there’s not a chance that there’s a single organization that hasn’t enacted harm.

“I know people are thinking very carefully and very deeply about the statements about racism. But it’s not clear who they’re speaking to. I think they’re speaking to the general world. So they want them to know that, hey, we see bad things are happening. They’re not speaking to the people who are most harmed. They’re not speaking directly to Black people. Most of the institutions don’t even say ‘Black people,’ it’s vague things like ‘injustice’ and ‘protest.’ Who are you talking to? That’s not for us.”

There’s no easy solution, and classical music is not alone in dealing with a racist legacy. But we in the arts are by and large a sensitive bunch. We can admit that we’ve done harm and have been complicit in doing harm. We can stop pretending that Black people, or any other excluded people, should mistake our feeling bad for real change. Because it isn’t real change. Not while any single person in this country has to wonder if they’ve been excluded from reaching their full potential because of the color of their skin, and certainly not while anyone in this country has to worry about their very survival.

The protests will die down, the pandemic could end. We’ve been given the challenge of reinventing our organizations and we’ve been given plenty of time for self-reflection. What will we do next?

Learn more about the 2020-2021 Project Inclusion Freeman Fellowship class.

NewCity | Orchestrating Change: Chicago Sinfonietta Confronts Racial Bias In Classical Music

As in the wake of the MeToo movement, classical music is having to confront a legacy most organizations would prefer not to talk about—in this case, a long legacy of racial exclusion in nearly every area, from the stage to key administrative and management positions.

Chicago Sinfonietta Announces New CEO

BLAKE-ANTHONY JOHNSON APPOINTED CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER

The first African American executive to guide a nationally renowned orchestra, in May 2020 Blake-Anthony Johnson was named Chief Executive Officer at the age of 29 of the award-winning Chicago Sinfonietta, an organization acclaimed as a cultural leader in the field and a powerful champion of diversity, equity and inclusion. A civically engaged leader who sits on the Steering Committee of Chicago Musical Pathways Initiative, he is also a champion of arts education, and is a member of the Faculty at Roosevelt University’s Chicago Conservatory of Performing Arts. Additionally, Mr. Johnson is a Trustee and Advisory Board Member for several organizations across the country that focus on criminal justice reform, healthcare, eliminating intergenerational poverty.

A former professional cellist who has performed with ensembles such as the New World Symphony, Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, and Nashville Symphony in the US, Chineke! Orchestra in the UK, and Poland’s Sinfonietta Polonia, as well as at music festivals including Spoleto Music Festival USA, Brevard Music Festival and Aix-en-Provence Music Festival, Mr. Johnson’s focus on arts administration and education began while he was a music student at Vanderbilt University’s Blair School of Music.

During his junior year at Blair School of Music in 2010-11, Mr. Johnson founded and served as Program Director of Classical Cake, a free concert series aimed at introducing first time audience members to a diverse spectrum of music in concerts that ranged from salon size performances with local artists to partnerships with large ensembles on tour in the Nashville area. Following the success of Classical Cake, he expanded his concept, creating the Music Education for Youth Initiative, serving as Founding Director and fostering meaningful exchange between the Nashville Symphony, W.O Smith School, and Vanderbilt University students with underprivileged youth within the Nashville community for several years. Later positions include serving as Assistant Personnel Manager of the Spoleto Music Festival USA and recently, as Director of Learning and Community for Louisville Orchestra, and as an Arts Advisory Council Member in Louisville, Kentucky. Other organizations with which Mr. Johnson has worked in the area of arts education and outreach include Carnegie Hall’s Weill Music Institute, El Sistema, and the Academia Filarmónica de Medellín.

A native of Atlanta, Georgia, Blake-Anthony Johnson holds a MM from Cleveland State University, a BM from Vanderbilt University, Blair School of Music, and a certificate from Manhattan School of Music in Orchestral Performance. Further professional training includes participation in the Sphinx Organization’s two year arts leadership program LEAD (Leaders in Excellence, Arts & Diversity, 2019-present), workshops in education, community engagement and collective bargaining at The League of American Orchestra’s 2018 Conference and a Certificate of Study in American Law from the University of Pennsylvania.

“I am thrilled to be part of the Chicago Sinfonietta team,” said Johnson, 29, in a statement. “Chicago Sinfonietta is a national treasure that over the past 32 seasons has contributed a great deal to our field and the city of Chicago. The vision of (Sinfonietta founder) maestro Paul Freeman has created an incredible organization that has been unmatched in the representation and celebration of equity, diversity and inclusion in a meaningful way. It is a legacy and tradition that I’m honored to continue with our amazing musicians, staff, board and music director Mei-Ann Chen,” said Blake-Anthony Johnson in an interview with the Chicago Tribune.

A Conversation With Jennifer Koh

JENNIFER KOH IS A VIRTUOSO MUSICIAN, BUT THAT ONLY BEGINS TO TELL HER STORY.

The Korean-American violinist is a force for change and diversity in classical music through her commissioning projects (The New American Concerto, Limitless, and Bridge to Beethoven, among others) and multimedia collaborations. She is also the Founder and Artistic Director of arco collaborative, an artist-driven nonprofit that fosters a better understanding of our world through musical dialogue inspired by ideas and the communities around us.

We sat with her to talk about her inspirations, career and Syzygy, a world-premiere commission by New Orleans-based composer Courtney Bryan written specifically for Koh, just in time for Chicago Sinfonietta’s spring concert Sight + Sound.

While there are plenty of violinists who are featured soloists with orchestras, there are less who are exploring what music means today in the world and actively pursuing those narratives. What first motivated you to take that expanded view?

While there are plenty of violinists who are featured soloists with orchestras, there are less who are exploring what music means today in the world and actively pursuing those narratives. What first motivated you to take that expanded view?

When I first entered classical music, people were talking about “the death of classical music.” I questioned why that was. Classical music is emotionally visceral and have always thought that classical music reflects who we are emotionally. One of the things about the arts is that in experiencing them, whether it’s through music or a book or a painting, you can leave your everyday existence and engage with people totally different than you. A lot of my work has to do with me asking myself, “How can I best serve my community and my art form?” Classical music is rooted in Europe in a time with certain customs and attitudes, but society has changed, and this art form is a place in which we can advocate for compelling stories that haven’t been heard before. It is a loss to all of us when we don’t hear from those other voices.

Tell me more about what you are trying to accomplish with Syzygy and other commissions where you’ve worked with visionary composers.

I want to reflect what America is today and advocate for great artistic composers who really have something to say and haven’t been heard in the form of a violin concerto. There is something especially compelling about that form, if for no other reason than the violin is the only instrument in the orchestra that has two entire sections. The standard definition of a violin concerto is solo violin and orchestra, but I think that the composers that I’ve worked with so far have really played with that notion and can expand that definition.

The first of your New American Concerto commissions was with someone who is known primarily in the jazz world and the second was a contemporary music composer. With Courtney Bryan, you’re working with someone who comfortably straddles both worlds. Is this a conscious progression?

The first of your New American Concerto commissions was with someone who is known primarily in the jazz world and the second was a contemporary music composer. With Courtney Bryan, you’re working with someone who comfortably straddles both worlds. Is this a conscious progression?

I don’t look at the world of music in terms of genre. I look at it in terms of great artists. The idea of genre never comes into play for me. All of the composers and artists that I work with have something intriguing to say artistically. And while everything starts with music, I also want to reflect the cultural and social concerns of our time and give voice to ideas that might not have been heard in concert halls before.

How does a commissioning project work? Is it a step-by-step collaboration, or does the composer present you a completed work?

It’s a process. I’m always researching and attending live performances by artists I’m interested in working with. I first head Courtney Bryan’s work at a festival that I was performing at. I was really struck by the storytelling aspect and emotional journey that she is able to create in her writing. I introduced myself and we started conversing via e-mail and phone, then met again in person. Once I issued the commission, another process begins. We study scores together and talk about what a violin concerto is and its particular challenges. We’ve already met several times and will continue to do so between now and the public premiere.

Syzygy will be premiered at the Sinfonietta’s themed Sight + Sound concert. Are you planning a visual component or multimedia work?

I’ve enjoyed working on many multimedia projects, but with these commissions I think it’s important to give the composers the space to work in purely musical terms without the added stress of accommodating an extra component. The music deserves its own premiere.

—Don Macica, contributing writer

Joel Thompson’s “Seven Last Words of the Unarmed”

In November of 2014, a Staten Island grand jury chose not to indict the officer whose actions led to the death of Eric Garner. To me, the message was clear.

Any doubts I had seemed to evaporate. If I were to be killed in some interaction with authority figures, my loved ones should not expect justice. There could be a video recording of my futile attempts to describe my distress – “I can’t breathe” – with the arm of the law around my neck and the life fading from my eyes, and still, my death wouldn’t matter. My death wouldn’t matter enough to warrant a formal charge of even manslaughter or negligent homicide. This was not an isolated incident – this was a trend. The color of my skin is a capital offence. To me, the message was clear. Any doubts I had seemed to evaporate. If I were to be killed in some interaction with authority figures, my loved ones should not expect justice. There could be a video recording of my futile attempts to describe my distress – “I can’t breathe” – with the arm of the law around my neck and the life fading from my eyes, and still, my death wouldn’t matter. My death wouldn’t matter enough to warrant a formal charge of even manslaughter or negligent homicide. This was not an isolated incident – this was a trend. The color of my skin is a capital offence.

Any doubts I had seemed to evaporate. If I were to be killed in some interaction with authority figures, my loved ones should not expect justice. There could be a video recording of my futile attempts to describe my distress – “I can’t breathe” – with the arm of the law around my neck and the life fading from my eyes, and still, my death wouldn’t matter. My death wouldn’t matter enough to warrant a formal charge of even manslaughter or negligent homicide. This was not an isolated incident – this was a trend. The color of my skin is a capital offence. To me, the message was clear. Any doubts I had seemed to evaporate. If I were to be killed in some interaction with authority figures, my loved ones should not expect justice. There could be a video recording of my futile attempts to describe my distress – “I can’t breathe” – with the arm of the law around my neck and the life fading from my eyes, and still, my death wouldn’t matter. My death wouldn’t matter enough to warrant a formal charge of even manslaughter or negligent homicide. This was not an isolated incident – this was a trend. The color of my skin is a capital offence.

Seven Last Words of the Unarmed wasn’t written to be heard. It was essentially a sonic diary entry expressing my fear, anger, and grief in the wake of this tragedy. I was serving as director of choral studies and assistant professor of music at Andrew College in Cuthbert, Georgia and my musical life mostly consisted of conducting and piano, but I occasionally composed pieces and hid them away. Finishing this work in early January 2015 was a much-needed catharsis; I felt exorcised of the emotions that had drained my spirit. However, Freddie Gray’s death the following April urged me to try to bring Seven Last Words of the Unarmed to life. A Facebook post asking musician friends to sightread the work, a phone call by a friend to Dr. Eugene Rogers of the University of Michigan, a commission from Andre Dowell to fully orchestrate the work for the 20th anniversary of the Sphinx Organization, and the piece is alive five years later and I am very grateful.

Seven Last Words of the Unarmed wasn’t written to be heard. It was essentially a sonic diary entry expressing my fear, anger, and grief in the wake of this tragedy. I was serving as director of choral studies and assistant professor of music at Andrew College in Cuthbert, Georgia and my musical life mostly consisted of conducting and piano, but I occasionally composed pieces and hid them away. Finishing this work in early January 2015 was a much-needed catharsis; I felt exorcised of the emotions that had drained my spirit. However, Freddie Gray’s death the following April urged me to try to bring Seven Last Words of the Unarmed to life. A Facebook post asking musician friends to sightread the work, a phone call by a friend to Dr. Eugene Rogers of the University of Michigan, a commission from Andre Dowell to fully orchestrate the work for the 20th anniversary of the Sphinx Organization, and the piece is alive five years later and I am very grateful.

Liturgical settings of the Seven Last Words of Christ are not attempting to demonize the Roman soldiers that orchestrated the crucifixion, but they are designed to stir within the listener an empathy towards the suffering of Jesus. Similarly, this piece is not an anti-police protest work; it is really a meditation on the lives of these black men and an effort to focus on their humanity, which is often eradicated in the media to justify their deaths.

Listening to Seven Last Words of the Unarmed can be uncomfortable. As you listen, I ask that you try to remain open. It can be easy to let a spirit of defensiveness pollute the experience of the piece. I ask that you revisit the last moments of these men with fresh hearts:

- the retired Marine who accidentally pressed his Life Alert necklace which recorded the police calling him a n***er before he was killed,

- the teenage boy with his bag of Skittles being chased in his own neighborhood,

- the young immigrant who called his mother in Guinea after he had saved up enough money to pursue a degree in computer science,

- the recent high school graduate and amateur musician whose body lay baking in the street for four hours before being taken to the coroner,

- the young father (of a 4-year-old girl) who was shot in the back while handcuffed in a prone position at Fruitvale Station,

- the other young father who was purchasing a BB gun for his son in a Wal-Mart in the open carry state of Ohio, and

- the 43-year-old grandfather who was choked to death on camera on the streets of New York City.

When the music is over, let us continue to listen. Let us listen to each other with love and hope for a more just future. Thank you.

With love,

Joel Thompson

Roy Kinsey

We had the pleasure of speaking with Roy Kinsey. Roy works as a librarian over in Chicago’s Austin Neighborhood and shares how identifying as a musician has changed his perspective on life and some of the best places in Austin to grab a bite and relax.

We had the pleasure of speaking with Roy Kinsey. Roy works as a librarian over in Chicago’s Austin Neighborhood and shares how identifying as a musician has changed his perspective on life and some of the best places in Austin to grab a bite and relax.

What are 2-3 areas in the neighborhood that you frequent and why?

I spend a lot of time working as a librarian at the public library in Austin; often listening to choir rehearsals on Mondays and Wednesday or the regular monthly open-mics that we hold here. The library’s auditorium has the best acoustics for live music and sounds amazing for people who sing, play instruments, or simply come to speak.

Let me also tell you about The Jerk Shop Restaurant on Chicago. This place is DIVINE! They have a unique and extensive menu of jerk chicken, steak, or shrimp dishes, and make the most incredible Jerk baked potato! It’s an absolute stop that you have to make if you are ever hungry on the west-side.

The swimming pool in the Austin Town-hall is pretty incredible as well. If you ever would like to take a solo swim, this is the perfect place to relax. The pool is newly renovated, yet still holds its charm and personality. Many of the buildings in Austin are old which adds a certain character to the neighborhood and spaces. The detailed architecture makes you understand that you are in a special place that has stood the tests of time.

What piece music or art would you say most reflects you and why?

My latest album Blackie best describes me . It released last year, and took a lifetime to make. At that point in my career, I really got to know myself and cleared a path to call myself an artist. Taking on the responsibility of an artist, meant being honest ,not only in my music, but with myself, about myself, and with the world around me.

I’m so grateful for the way that album has changed my life. I have come to understand the importance of family and community, while understanding my individuality as well. The album is deeply Chicago, American, and honors my grandmother for the many sacrifices made so that I can enjoy the life that I am living. It was a wonderful album to create and I how it asks me to grow with it.

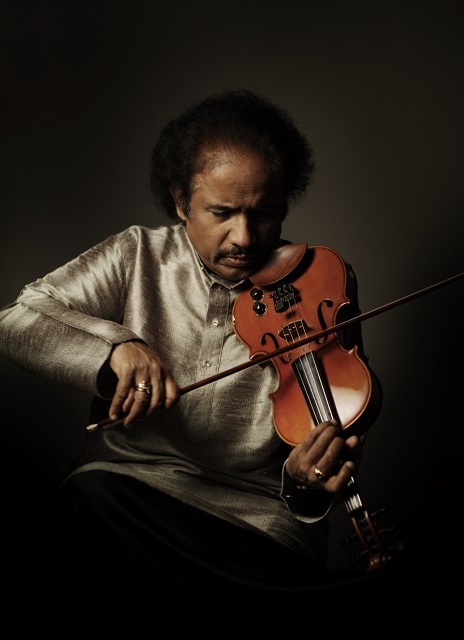

A Conversation With Dr. L. Subramaniam

Dr. L. Subramaniam is considered one of the most outstanding Indian classical violinists, but he has also established himself as one of the foremost Indian composers in the realm of orchestral music.

He has recorded, played, and composed a variety of music including South Indian Carnatic, Western classical, jazz, world fusion, and world music. We spoke with Subramaniam about his masterful intersection of Indian and Western music, his many artistic collaborations, and his upcoming performance of Shanti Priya with the Chicago Sinfonietta.

Is the violin a western instrument adapted for Indian classical music? If so, what are the features of it that make it well suited to that purpose?

Is the violin a western instrument adapted for Indian classical music? If so, what are the features of it that make it well suited to that purpose?

There have always been many stringed and bowed instruments in Indian music, but the violin came in during the British rule. It was eventually adapted into Indian classical music because it was well-suited to accompany the human voice. At a time when there were no mics, it was especially useful to have an instrument whose volume could match the singer’s. The violin has no frets, which made it easier to slide a bow across it smoothly. This also meant the instrumentalist could sustain a note as long as they wanted.

For these reasons, the violin was and continues to be the primary accompanying instrument in Carnatic music. In the early 20th century, my father, Professor V. Lakshminarayana, introduced a technique that violinists could use to play solo; he developed different methods that made the violin stand out as distinct from the singer’s voice while still retaining its voice-like qualities.

What are the main characteristics of Carnatic music tradition, and how are they applied to Western orchestras?

The two most important concepts of Carnatic music are raga and tala; each raga is based on a scale and each tala is a rhythmic cycle or time signature. Possibly the most identifiable aspect of Carnatic music, however, are the slides we use (called gamakas). Each raga has its own gamaka, or ornamentations. The challenge is to take these elements and use it in an orchestral context while also maintaining the individuality of a symphony orchestra.

The idea here is not to make an orchestra play Indian music, but to create something where both Western and Indian musicians feel like they’re playing their own music while creating something unique. With this context, we combine elements of Carnatic music with parts of Western classical music (like harmony and counterpoint) to build something entirely original.

What makes an artist someone who you want to work with?

The artist’s music should be something I enjoy for what it is. Second, they should be open to trying new things. In a new collaboration, it is natural to have to step out of your comfort zone and experiment a little. I need to know that the musicians I’m working with are receptive enough to new and exciting ideas going forward, as I certainly will be.

Shanti Priya is a violin concerto for peace and harmony. In what way are you conveying that message?

Shanti Priya is a violin concerto for peace and harmony. In what way are you conveying that message?

The words “shanti priya” mean “lover of peace,” and that mood is brought in throughout the piece. The first and second movements are meditative in their approach, and the scales we have chosen reflect that. The third movement is an upbeat piece, but it retains an uplifting theme even though there are many fast and virtuosic passages. No part of the piece is brash or aggressive in its approach, and that was something I was careful to convey.

You’ll be performing Shanti Priya in the Chicago Sinfonietta concert that celebrates Diwali. How are Shanti Priya‘s themes reflective of the holiday’s meaning and what can Western audiences take from that?

Diwali celebrates the triumph of light over darkness and knowledge over ignorance. Every festival is a celebration of the gift of life itself. This piece has meditative, contemplative passages as well as more upbeat, celebratory ones. I hope a Western audience can find the essence of our festivals in this piece; a blend of reflection, prayer, and celebration.

—Don Macica, contributing writer

Dr. Subramaniam will be performing his concerto Shanti Priya on the Sinfonietta’s Diwali concert, Love + Light. Get your tickets here!