As in the wake of the MeToo movement, classical music is having to confront a legacy most organizations would prefer not to talk about—in this case, a long legacy of racial exclusion in nearly every area, from the stage to key administrative and management positions.

Author: CMO

NewCity | Orchestrating Change: Chicago Sinfonietta Confronts Racial Bias In Classical Music

Chicago Sinfonietta Announces New CEO

BLAKE-ANTHONY JOHNSON APPOINTED CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER

The first African American executive to guide a nationally renowned orchestra, in May 2020 Blake-Anthony Johnson was named Chief Executive Officer at the age of 29 of the award-winning Chicago Sinfonietta, an organization acclaimed as a cultural leader in the field and a powerful champion of diversity, equity and inclusion. A civically engaged leader who sits on the Steering Committee of Chicago Musical Pathways Initiative, he is also a champion of arts education, and is a member of the Faculty at Roosevelt University’s Chicago Conservatory of Performing Arts. Additionally, Mr. Johnson is a Trustee and Advisory Board Member for several organizations across the country that focus on criminal justice reform, healthcare, eliminating intergenerational poverty.

A former professional cellist who has performed with ensembles such as the New World Symphony, Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, and Nashville Symphony in the US, Chineke! Orchestra in the UK, and Poland’s Sinfonietta Polonia, as well as at music festivals including Spoleto Music Festival USA, Brevard Music Festival and Aix-en-Provence Music Festival, Mr. Johnson’s focus on arts administration and education began while he was a music student at Vanderbilt University’s Blair School of Music.

During his junior year at Blair School of Music in 2010-11, Mr. Johnson founded and served as Program Director of Classical Cake, a free concert series aimed at introducing first time audience members to a diverse spectrum of music in concerts that ranged from salon size performances with local artists to partnerships with large ensembles on tour in the Nashville area. Following the success of Classical Cake, he expanded his concept, creating the Music Education for Youth Initiative, serving as Founding Director and fostering meaningful exchange between the Nashville Symphony, W.O Smith School, and Vanderbilt University students with underprivileged youth within the Nashville community for several years. Later positions include serving as Assistant Personnel Manager of the Spoleto Music Festival USA and recently, as Director of Learning and Community for Louisville Orchestra, and as an Arts Advisory Council Member in Louisville, Kentucky. Other organizations with which Mr. Johnson has worked in the area of arts education and outreach include Carnegie Hall’s Weill Music Institute, El Sistema, and the Academia Filarmónica de Medellín.

A native of Atlanta, Georgia, Blake-Anthony Johnson holds a MM from Cleveland State University, a BM from Vanderbilt University, Blair School of Music, and a certificate from Manhattan School of Music in Orchestral Performance. Further professional training includes participation in the Sphinx Organization’s two year arts leadership program LEAD (Leaders in Excellence, Arts & Diversity, 2019-present), workshops in education, community engagement and collective bargaining at The League of American Orchestra’s 2018 Conference and a Certificate of Study in American Law from the University of Pennsylvania.

“I am thrilled to be part of the Chicago Sinfonietta team,” said Johnson, 29, in a statement. “Chicago Sinfonietta is a national treasure that over the past 32 seasons has contributed a great deal to our field and the city of Chicago. The vision of (Sinfonietta founder) maestro Paul Freeman has created an incredible organization that has been unmatched in the representation and celebration of equity, diversity and inclusion in a meaningful way. It is a legacy and tradition that I’m honored to continue with our amazing musicians, staff, board and music director Mei-Ann Chen,” said Blake-Anthony Johnson in an interview with the Chicago Tribune.

A Conversation With Jennifer Koh

JENNIFER KOH IS A VIRTUOSO MUSICIAN, BUT THAT ONLY BEGINS TO TELL HER STORY.

The Korean-American violinist is a force for change and diversity in classical music through her commissioning projects (The New American Concerto, Limitless, and Bridge to Beethoven, among others) and multimedia collaborations. She is also the Founder and Artistic Director of arco collaborative, an artist-driven nonprofit that fosters a better understanding of our world through musical dialogue inspired by ideas and the communities around us.

We sat with her to talk about her inspirations, career and Syzygy, a world-premiere commission by New Orleans-based composer Courtney Bryan written specifically for Koh, just in time for Chicago Sinfonietta’s spring concert Sight + Sound.

While there are plenty of violinists who are featured soloists with orchestras, there are less who are exploring what music means today in the world and actively pursuing those narratives. What first motivated you to take that expanded view?

While there are plenty of violinists who are featured soloists with orchestras, there are less who are exploring what music means today in the world and actively pursuing those narratives. What first motivated you to take that expanded view?

When I first entered classical music, people were talking about “the death of classical music.” I questioned why that was. Classical music is emotionally visceral and have always thought that classical music reflects who we are emotionally. One of the things about the arts is that in experiencing them, whether it’s through music or a book or a painting, you can leave your everyday existence and engage with people totally different than you. A lot of my work has to do with me asking myself, “How can I best serve my community and my art form?” Classical music is rooted in Europe in a time with certain customs and attitudes, but society has changed, and this art form is a place in which we can advocate for compelling stories that haven’t been heard before. It is a loss to all of us when we don’t hear from those other voices.

Tell me more about what you are trying to accomplish with Syzygy and other commissions where you’ve worked with visionary composers.

I want to reflect what America is today and advocate for great artistic composers who really have something to say and haven’t been heard in the form of a violin concerto. There is something especially compelling about that form, if for no other reason than the violin is the only instrument in the orchestra that has two entire sections. The standard definition of a violin concerto is solo violin and orchestra, but I think that the composers that I’ve worked with so far have really played with that notion and can expand that definition.

The first of your New American Concerto commissions was with someone who is known primarily in the jazz world and the second was a contemporary music composer. With Courtney Bryan, you’re working with someone who comfortably straddles both worlds. Is this a conscious progression?

The first of your New American Concerto commissions was with someone who is known primarily in the jazz world and the second was a contemporary music composer. With Courtney Bryan, you’re working with someone who comfortably straddles both worlds. Is this a conscious progression?

I don’t look at the world of music in terms of genre. I look at it in terms of great artists. The idea of genre never comes into play for me. All of the composers and artists that I work with have something intriguing to say artistically. And while everything starts with music, I also want to reflect the cultural and social concerns of our time and give voice to ideas that might not have been heard in concert halls before.

How does a commissioning project work? Is it a step-by-step collaboration, or does the composer present you a completed work?

It’s a process. I’m always researching and attending live performances by artists I’m interested in working with. I first head Courtney Bryan’s work at a festival that I was performing at. I was really struck by the storytelling aspect and emotional journey that she is able to create in her writing. I introduced myself and we started conversing via e-mail and phone, then met again in person. Once I issued the commission, another process begins. We study scores together and talk about what a violin concerto is and its particular challenges. We’ve already met several times and will continue to do so between now and the public premiere.

Syzygy will be premiered at the Sinfonietta’s themed Sight + Sound concert. Are you planning a visual component or multimedia work?

I’ve enjoyed working on many multimedia projects, but with these commissions I think it’s important to give the composers the space to work in purely musical terms without the added stress of accommodating an extra component. The music deserves its own premiere.

—Don Macica, contributing writer

Joel Thompson’s “Seven Last Words of the Unarmed”

In November of 2014, a Staten Island grand jury chose not to indict the officer whose actions led to the death of Eric Garner. To me, the message was clear.

Any doubts I had seemed to evaporate. If I were to be killed in some interaction with authority figures, my loved ones should not expect justice. There could be a video recording of my futile attempts to describe my distress – “I can’t breathe” – with the arm of the law around my neck and the life fading from my eyes, and still, my death wouldn’t matter. My death wouldn’t matter enough to warrant a formal charge of even manslaughter or negligent homicide. This was not an isolated incident – this was a trend. The color of my skin is a capital offence. To me, the message was clear. Any doubts I had seemed to evaporate. If I were to be killed in some interaction with authority figures, my loved ones should not expect justice. There could be a video recording of my futile attempts to describe my distress – “I can’t breathe” – with the arm of the law around my neck and the life fading from my eyes, and still, my death wouldn’t matter. My death wouldn’t matter enough to warrant a formal charge of even manslaughter or negligent homicide. This was not an isolated incident – this was a trend. The color of my skin is a capital offence.

Any doubts I had seemed to evaporate. If I were to be killed in some interaction with authority figures, my loved ones should not expect justice. There could be a video recording of my futile attempts to describe my distress – “I can’t breathe” – with the arm of the law around my neck and the life fading from my eyes, and still, my death wouldn’t matter. My death wouldn’t matter enough to warrant a formal charge of even manslaughter or negligent homicide. This was not an isolated incident – this was a trend. The color of my skin is a capital offence. To me, the message was clear. Any doubts I had seemed to evaporate. If I were to be killed in some interaction with authority figures, my loved ones should not expect justice. There could be a video recording of my futile attempts to describe my distress – “I can’t breathe” – with the arm of the law around my neck and the life fading from my eyes, and still, my death wouldn’t matter. My death wouldn’t matter enough to warrant a formal charge of even manslaughter or negligent homicide. This was not an isolated incident – this was a trend. The color of my skin is a capital offence.

Seven Last Words of the Unarmed wasn’t written to be heard. It was essentially a sonic diary entry expressing my fear, anger, and grief in the wake of this tragedy. I was serving as director of choral studies and assistant professor of music at Andrew College in Cuthbert, Georgia and my musical life mostly consisted of conducting and piano, but I occasionally composed pieces and hid them away. Finishing this work in early January 2015 was a much-needed catharsis; I felt exorcised of the emotions that had drained my spirit. However, Freddie Gray’s death the following April urged me to try to bring Seven Last Words of the Unarmed to life. A Facebook post asking musician friends to sightread the work, a phone call by a friend to Dr. Eugene Rogers of the University of Michigan, a commission from Andre Dowell to fully orchestrate the work for the 20th anniversary of the Sphinx Organization, and the piece is alive five years later and I am very grateful.

Seven Last Words of the Unarmed wasn’t written to be heard. It was essentially a sonic diary entry expressing my fear, anger, and grief in the wake of this tragedy. I was serving as director of choral studies and assistant professor of music at Andrew College in Cuthbert, Georgia and my musical life mostly consisted of conducting and piano, but I occasionally composed pieces and hid them away. Finishing this work in early January 2015 was a much-needed catharsis; I felt exorcised of the emotions that had drained my spirit. However, Freddie Gray’s death the following April urged me to try to bring Seven Last Words of the Unarmed to life. A Facebook post asking musician friends to sightread the work, a phone call by a friend to Dr. Eugene Rogers of the University of Michigan, a commission from Andre Dowell to fully orchestrate the work for the 20th anniversary of the Sphinx Organization, and the piece is alive five years later and I am very grateful.

Liturgical settings of the Seven Last Words of Christ are not attempting to demonize the Roman soldiers that orchestrated the crucifixion, but they are designed to stir within the listener an empathy towards the suffering of Jesus. Similarly, this piece is not an anti-police protest work; it is really a meditation on the lives of these black men and an effort to focus on their humanity, which is often eradicated in the media to justify their deaths.

Listening to Seven Last Words of the Unarmed can be uncomfortable. As you listen, I ask that you try to remain open. It can be easy to let a spirit of defensiveness pollute the experience of the piece. I ask that you revisit the last moments of these men with fresh hearts:

- the retired Marine who accidentally pressed his Life Alert necklace which recorded the police calling him a n***er before he was killed,

- the teenage boy with his bag of Skittles being chased in his own neighborhood,

- the young immigrant who called his mother in Guinea after he had saved up enough money to pursue a degree in computer science,

- the recent high school graduate and amateur musician whose body lay baking in the street for four hours before being taken to the coroner,

- the young father (of a 4-year-old girl) who was shot in the back while handcuffed in a prone position at Fruitvale Station,

- the other young father who was purchasing a BB gun for his son in a Wal-Mart in the open carry state of Ohio, and

- the 43-year-old grandfather who was choked to death on camera on the streets of New York City.

When the music is over, let us continue to listen. Let us listen to each other with love and hope for a more just future. Thank you.

With love,

Joel Thompson

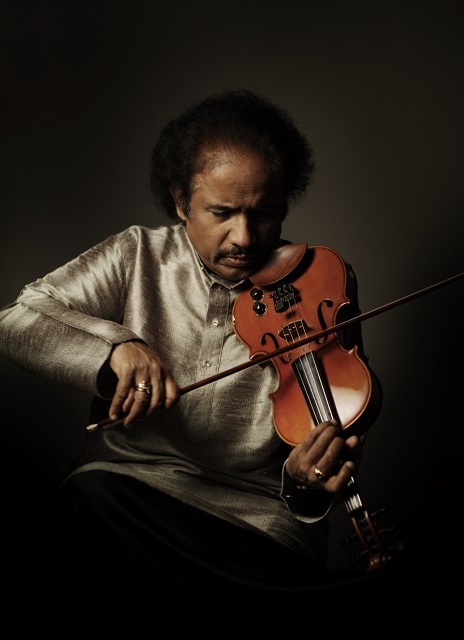

A Conversation With Dr. L. Subramaniam

Dr. L. Subramaniam is considered one of the most outstanding Indian classical violinists, but he has also established himself as one of the foremost Indian composers in the realm of orchestral music.

He has recorded, played, and composed a variety of music including South Indian Carnatic, Western classical, jazz, world fusion, and world music. We spoke with Subramaniam about his masterful intersection of Indian and Western music, his many artistic collaborations, and his upcoming performance of Shanti Priya with the Chicago Sinfonietta.

Is the violin a western instrument adapted for Indian classical music? If so, what are the features of it that make it well suited to that purpose?

Is the violin a western instrument adapted for Indian classical music? If so, what are the features of it that make it well suited to that purpose?

There have always been many stringed and bowed instruments in Indian music, but the violin came in during the British rule. It was eventually adapted into Indian classical music because it was well-suited to accompany the human voice. At a time when there were no mics, it was especially useful to have an instrument whose volume could match the singer’s. The violin has no frets, which made it easier to slide a bow across it smoothly. This also meant the instrumentalist could sustain a note as long as they wanted.

For these reasons, the violin was and continues to be the primary accompanying instrument in Carnatic music. In the early 20th century, my father, Professor V. Lakshminarayana, introduced a technique that violinists could use to play solo; he developed different methods that made the violin stand out as distinct from the singer’s voice while still retaining its voice-like qualities.

What are the main characteristics of Carnatic music tradition, and how are they applied to Western orchestras?

The two most important concepts of Carnatic music are raga and tala; each raga is based on a scale and each tala is a rhythmic cycle or time signature. Possibly the most identifiable aspect of Carnatic music, however, are the slides we use (called gamakas). Each raga has its own gamaka, or ornamentations. The challenge is to take these elements and use it in an orchestral context while also maintaining the individuality of a symphony orchestra.

The idea here is not to make an orchestra play Indian music, but to create something where both Western and Indian musicians feel like they’re playing their own music while creating something unique. With this context, we combine elements of Carnatic music with parts of Western classical music (like harmony and counterpoint) to build something entirely original.

What makes an artist someone who you want to work with?

The artist’s music should be something I enjoy for what it is. Second, they should be open to trying new things. In a new collaboration, it is natural to have to step out of your comfort zone and experiment a little. I need to know that the musicians I’m working with are receptive enough to new and exciting ideas going forward, as I certainly will be.

Shanti Priya is a violin concerto for peace and harmony. In what way are you conveying that message?

Shanti Priya is a violin concerto for peace and harmony. In what way are you conveying that message?

The words “shanti priya” mean “lover of peace,” and that mood is brought in throughout the piece. The first and second movements are meditative in their approach, and the scales we have chosen reflect that. The third movement is an upbeat piece, but it retains an uplifting theme even though there are many fast and virtuosic passages. No part of the piece is brash or aggressive in its approach, and that was something I was careful to convey.

You’ll be performing Shanti Priya in the Chicago Sinfonietta concert that celebrates Diwali. How are Shanti Priya‘s themes reflective of the holiday’s meaning and what can Western audiences take from that?

Diwali celebrates the triumph of light over darkness and knowledge over ignorance. Every festival is a celebration of the gift of life itself. This piece has meditative, contemplative passages as well as more upbeat, celebratory ones. I hope a Western audience can find the essence of our festivals in this piece; a blend of reflection, prayer, and celebration.

—Don Macica, contributing writer

Dr. Subramaniam will be performing his concerto Shanti Priya on the Sinfonietta’s Diwali concert, Love + Light. Get your tickets here!

A World Endangered – Interview with Michelle Isaac and Clarice Assad

At a moment in our history when conservation is crucial and time is of the essence, Chicago Sinfonietta seeks to illuminate environmental change through the power of symphonic music. Forces + Fates, the orchestra’s first conversation of the season, explores the volatility of our planet, and how its future rests solely in the hands of the human race.

Two of the concert’s featured composers, Clarice Assad (Nhanderu) and Michelle Isaac (Earth Tryptich, with Stefan L. Smith and Fernando Arroyo Lascurain), discuss the creative impetus for this environment-themed concert, and how the same priority for planetary preservation extends to the lifeblood of classical music.

Why is classical music such a powerful tool for you, creatively?

Clarice: I think I can say more with music than I can say with words sometimes. That’s the way that I grew up. Starting with a theme or idea following a storyline or motion – trying to play with that within the music if that makes any sense. With classical music, I can paint a picture of what I’m passionate about, what fuels me, what inspires me.

How does that passion relate to this environmental concert in particular?

C: I was always fascinated by Native American culture, and I really identify with the native cultures of Brazil. The Amazon, the tribes that were there – I studied a lot of their music, and I really enjoyed all of their beautiful rituals with the rain, calling it to help with their crops. It’s worshiping, really. They’re asking for help, getting nature to work with them without trying to manipulate it. I wanted to recreate that in the music. One thing I found effective was to get the orchestra to chant and perform with some effects that would sound like rain falling.

What does your creative process look like at present?

Michelle: I’m trying to nail down my creative process. It’s a lot of trial and error. For this piece, I started by just reading really depressing news articles about the state of the planet. I tend to draw a lot of pictures, doodles, and graphs. I write out prose to get ideas going and end up brainstorming a lot of the emotions you feel when you read these things. Sometimes I build compositional structures off of those things, or I use that as a starting point for basic emotions I’m trying to get to. It’s all one big learning process for me right now, and hopefully it works!

Do you think the creative process shifts as you grow as a composer and musician?

C: Mine is still evolving. I think that it never stops evolving, and that’s the idea. I never like to repeat myself if I’m capable of doing so. I’ll try really hard not to do that. When it comes to orchestrating a passage, I always try to do something different. I get upset when I can’t, because oftentimes we tend to fall back on many things that we know work.

Michelle, we spoke a little about the background of Clarice’s piece and what’s she’s trying to convey. What kind of message are you trying to convey about the planet in your movement of Earth Triptych, both socially and musically?

M: The main message of my movement is a sense of urgency: the idea that we’re hitting a point of extremes not only in weather and temperatures, but also in human indifference. It is also extreme in the sense that we are running out of time to do anything about it. So musically, that’s also the impetus – it starts very slow and harmoniously, and makes people comfortable. By the end of it, it’s very aggressive and is written to make the audience feel very uncomfortable.

Clarice, are there components of Nhanderú that share the same outlook as Earth Triptych?

C: No, it’s different. I wasn’t thinking about climate change or anything like that. It’s more about nature evolving on its own. In a way, it’s the opposite of Michelle’s. It’s going back before all of this stuff started to happen and before we started mutilating the earth.

M: The first movement of Earth Triptych that Stefan is composing touches more on the sentiments of Clarice’s piece because it represents Earth before humans. The point of Earth Triptych is to show that there is beauty that we should be protecting. We depict the beauty, what we’re doing to it, and where we’re going to go from there. So, they’re two different snapshots of the same human-to-earth relationship – at different times, in different cultures, with different messaging.

What is the dynamic like in trying to get the movements of Earth Triptych to communicate with one another?

M: It’s pretty unusual for three composers to collaborate on one piece and make it sound cohesive. We’re still trying to figure out the best way to do that. At this point, it’s going to end up being a dialogue like any other, where different voices come to the table to discuss the same thing and hopefully find some common ground.

Are there parallels between the story that we’re telling about the earth and the state of classical music? Are there parallels regarding the evolution of this artform with the discussion that we’re having in the concert?

C: I think we’re not really damaging the Earth so much as we are damaging the capacity of life. We could disappear overnight, and the Earth would still be here, and it would probably be better off without us. We have to self-preserve. It’s kind of interesting because humans are usually very individualistic, and that’s not a good thing.

Going back to the state of classical music, everything is a little up in the air now, and yes, I think that we’re not listening. We’re not focusing because of all the information that we’ve got in our lives. This kind of music requires attention and listening, and that’s kind of a lost art form in a way. It absolutely links back to what is happening in our world. No one is stopping to listen and pay attention, and enjoy nature.

What steps should we be taking to preserve and evolve classical music?

C: It’s evolving no matter what. That’s the beauty of things that are struggling and have a hard time thriving. One thing to consider is the education system. It really needs attention as a whole. We learn things when we’re very young, and we learn values, we embrace what’s important, and we create habits. The fact that there’s no music in schools is pretty bad, the fact that we don’t really teach kids to preserve nature is really bad. It all goes hand in hand.

M: I absolutely agree. There are, in both the environmental and classical music movements, people who are doing the work, who are preserving, listening, and innovating. But it takes more than that if we want to see both come back to life in a more universal, global spread.

Just having this sort of dialogue in a concert hall is really important, and a really cool thing that Chicago Sinfonietta is doing. It’s not done very often. Maybe that’s the way to get people talking about both of these issues – the parallels between environmentalism and classical music and why we need both of them.

Both Nhanderú and Earth Triptych will be premiered on the first concert of our 2019-20 season, Forces + Fates. Get your tickets now!

Project Inclusion | Largest Project Inclusion Class to Date

Press Contact: Jim Hirsch

Press Contact: Jim Hirsch

Chicago Sinfonietta

312-284-1553

jhirsch@localhost

Chicago Sinfonietta Continues Its Commitment to Diversity

With Largest Project Inclusion Class to Date

CHICAGO (August 15, 2019) – In a continuation of its commitment to equity, inclusion, and changing the face of classical music, Chicago Sinfonietta has announced its incoming class for its groundbreaking Project Inclusion Freeman Fellowship Program (PI).

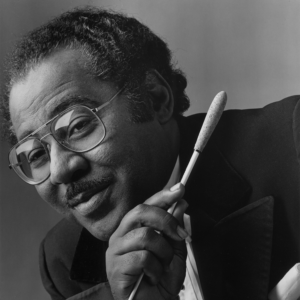

Now in its 12th year Chicago Sinfonietta founder Paul Freeman created Project Inclusion to provide mentorship and professional development to diverse and emerging musicians, conductors, and arts administrators. Freeman and CS staff thoughtfully designed the program, which has grown to three multifaceted fellowship tracks, to eliminate institutional bias due to ethnicity, race, and socioeconomics, in hopes of making classical music accessible to all. Chicago Sinfonietta’s PI fellows come from across the globe country to work closely with Music Director Mei-Ann Chen, staff members, CS musicians, and key supporters of the organization to gain hands-on experience to help them compete for and win jobs in U.S. orchestras. The Orchestra and Conducting Fellows will attend, conduct, and perform at Chicago Sinfonietta’s concerts throughout the 2019-2020 season, Dialogue.

“Nothing Chicago Sinfonietta does captures the legacy of our late founder, Maestro Paul Freeman, like the Project Inclusion Freeman Fellowship program,” said Chicago Sinfonietta CEO Jim Hirsch. “Paul had an incredible eye for talent and a life-long commitment to nurturing orchestral musicians, soloists, composers, and conductors from diverse backgrounds. This year’s class of Project Inclusion fellows would make Maestro proud and they will soon take their places on the stages and podiums of orchestras in the years to come.”

Former PI Conducting alumnus Jonathan Rush (left) will serve as Assistant Conductor for the 2019-2020 season, working alongside this year’s PI fellows and taking the podium at this year’s MLK Tribute Concert.

“I am so thrilled to serve as Assistant Conductor with the Sinfonietta,” said Rush. “It’s truly an honor to be able to continue in Maestro Freeman’s vision, alongside America’s most diverse orchestra. I’m excited to continue changing the faces of classical with my Chicago Sinfonietta family.”

The 2019-2020 Project Inclusion Freeman Conducting Fellows are Dr. Antoine T. Clark, Alexandra Enyart, and Aaron King Vaughan. Former PI Orchestral Fellow Kyle Dickson, along with newcomers Taichi Fukumura and Yabetza Vivas Irizarry, will serve as Auditors.

The 2019-2020 Project Inclusion Freeman Orchestral Fellows are Najette Abouelhadi (cello), Fahad Awan (violin), Alison Lovera (violin), and Seth Pae (viola).

“Project Inclusion is about diversity, talent, and developing talent without bias so that young, promising individuals can go on to contribute to what we see and hear on the world’s stages,” said Music Director Chen It is an honor to further Maestro Freeman’s ideals and nurture the incredible artists that are participating in the 2019-2020 fellowship program. Our past fellows have gone on to make their mark in the arts with major positions in the industry, and this season’s fellows hold the same promise. It is my dream come true to witness Maestro Freeman’s legacy being carried far and wide through the expansion of Sinfonietta’s fellowship program and how it impacts our industry in deep and meaningful ways!”

For more information about Project Inclusion, visit chicagosinfonietta.org

About the Sinfonietta

Now approaching its 32nd season, Chicago Sinfonietta continues to push artistic boundaries under the baton of Maestro Mei-Ann Chen and organizational leadership of Jim Hirsch and Courtney Perkins. The orchestra is dedicated to providing an alternative way of hearing, seeing and thinking about a symphony orchestra and promoting diversity, inclusion, racial and cultural equity in the arts. In 2016, Chicago Sinfonietta was the proud recipient of the 2016 Spirit of Innovation Award presented by the Chicago Innovation Awards as well as the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s prestigious MacArthur Award for Creative and Effective Institutions (MACEI). The MacArthur award recognizes exceptional organizations that are key contributors in their fields.

Chicago Sinfonietta is grateful to its 2019-2020 Project Inclusion supporters including: The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The Andrew W. Mellow Foundation, The Joyce Foundation, Crown Family Philanthropies, and technology supporter CDW.

Project Inclusion | A Brief History and Inside Perspective

CEO Jim Hirsch offers a historical deep dive and insider perspective in to the creation of Chicago Sinfonietta’s groundbreaking fellowship and education program.

“I just recently saw Hamilton for the second time and the song, “The Room Where It Happens,” has been running through my brain almost non-stop. But as I think about the very beginning of what has become one of Chicago Sinfonietta’s signature programs, Project Inclusion, it’s apropos because I was in the room where it happened! It all came about through a strategic planning process that we began in 2005. First, some background.

Maestro Freeman had a keen eye for finding talented musicians, composers, soloists, and conductors from diverse backgrounds. He had informally mentored and championed individuals throughout his career and helped launch some of the most accomplished artists of the time including Yo-Yo Ma, among others. As we brainstormed what we wanted to accomplish for the future in 2005, it became clear that to help address the dearth of diverse musicians in American orchestras, Chicago Sinfonietta needed to do something about it. We decided to create

a fellowship program that would take early career, diverse musicians and invite them to rehearse and perform with the orchestra for up to two years.

Maestro Freeman, Renee Baker (orchestra personnel manager at that time), and I worked as a team to create the initial program outlines for Project Inclusion. We held auditions and introduced the first class of Project Inclusion in January of 2007 during our MLK concert.

The program has been offered ever since and we added a conducting fellowship in 2014 and an administrative fellowship in 2015. When Maestro Freeman passed away we renamed it the Project Inclusion Freeman Fellowship in his honor. We are excited to have recently introduced the 2019-2020 class of Freeman Fellows who will begin their work with us in September and look forward to being in the room where it happens as they begin their career journeys.” —Jim Hirsch

Learn more about the 2019-2020 Project Inclusion Freeman Fellowship class.

Chicago Sinfonietta & Project W: Why are Female Composers Underrepresented?

“One US orchestra that has consistently championed diversity is the Chicago Sinfonietta. Music by women represented 42% of the repertoire it programmed for its 30th-anniversary season in 2017–18 and included four new commissions – from Brazilian–American composer Clarice Assad, African–American composer and violinist Jessie Montgomery, Indian–American composer Reena Esmail and the multi-award-winning Jennifer Higdon.”

Read more about Project W in The Strad’s full article!

The Woman at the Podium at the Chicago Sinfonietta

“Mei-Ann Chen, music director of Chicago Sinfonietta, which kicks off its 31st season Sept. 5 with a concert at the Jay Pritzker Pavilion at Millennium Park, wants to see more women in classical music.”

“Mei-Ann Chen, music director of Chicago Sinfonietta, which kicks off its 31st season Sept. 5 with a concert at the Jay Pritzker Pavilion at Millennium Park, wants to see more women in classical music.”

Crain’s Chicago Business interviewed our music director about women in music. Read more here!