[one_half]

[sws_button class=”” size=”sws_btn_medium” align=”center” href=”https://chicagosinfonietta.org/event/1213concert-ii/” target=”_blank” label=”Buy Tickets!” template=”sws_btn_default” textcolor=”FFFFFF” bgcolor=”ed901b” bgcolorhover=”c76114″] [/sws_button]

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

[sws_button class=”” size=”sws_btn_medium” align=”” href=”https://chicagosinfonietta.org/wp-content/uploads/Chicago-Sinfonietta-Dia-de-los-Muertos12.pdf” target=”_blank” label=”Program Notes” template=”sws_btn_default” textcolor=”FFFFFF” bgcolor=”ed901b” bgcolorhover=”c76114″] [/sws_button]

[/one_half_last]

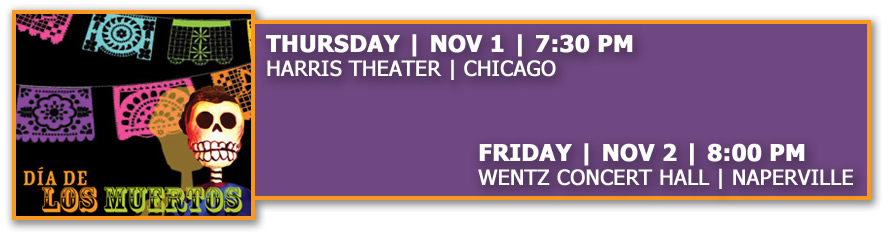

There are times when we reflect on those we have loved and lost, when we contemplate questions of life, beauty, and mortality. Throughout Latin America, but especially in Mexico and in Latino communities throughout the U.S., these somber reflections are balanced by joyful celebration of the lives of those who have departed. Our Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, concert finds that balance as well, combining the mournful and exuberant in ways that are equally reverent.

THE ARTISTS

[one_half]

Gisele Ben-Dor, conductor

Gisele Ben-Dor was born in Uruguay and immigrated to Israel in 1973. She graduated from the Rubin Academy of Music, Tel Aviv University and the Yale School of Music. As an active guest conductor and music director worldwide, she has had a crucial role in the rejuvenation and promotion of the music of Latin America, making her an ideal conductor to lead Día de los Muertos. She has championed music by Ginastera, Villa-Lobos, Revueltas, Piazzolla, and Luis Bacalov and is a founder of the Tango and Malambo Festival in Argentina as well as a festival dedicated to Mexican composer Silvestre Revueltas.

Gisele Ben-Dor was born in Uruguay and immigrated to Israel in 1973. She graduated from the Rubin Academy of Music, Tel Aviv University and the Yale School of Music. As an active guest conductor and music director worldwide, she has had a crucial role in the rejuvenation and promotion of the music of Latin America, making her an ideal conductor to lead Día de los Muertos. She has championed music by Ginastera, Villa-Lobos, Revueltas, Piazzolla, and Luis Bacalov and is a founder of the Tango and Malambo Festival in Argentina as well as a festival dedicated to Mexican composer Silvestre Revueltas.

She made her conducting debut with the Israel Philharmonic in Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, televised and broadcast by the BBC throughout Europe and Israel, as part of a series of master classes with Zubin Mehta.

Gisele Ben-Dor has her own website with photos, a discography, and audio samples.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

Of course, Maestro Ben-Dor is adept at the European canon as well. Here she is conducting a movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 4.

[/one_half_last]

NOTE: Because of the massive storm that hit the northeast, Raul Jaurena is unable to leave New York City and will not perform at Día de los Muertos. Changes have been made to the program because of Raul’s absence and some of the pieces mentioned below may be changed.

THE COMPOSERS

[one_half]

Manuel de Falla

La Vida Breve – Ritual Fire Dance from El Amor Brujo

The roots of Latin American music, both folkloric and classical, can of course be traced back to Europe and especially Spain. Manuel de Falla, perhaps Spain’s most important composer, used the flamenco tradition, which itself has roots in Arabic music, as the basis of several of his best known compositions.

The roots of Latin American music, both folkloric and classical, can of course be traced back to Europe and especially Spain. Manuel de Falla, perhaps Spain’s most important composer, used the flamenco tradition, which itself has roots in Arabic music, as the basis of several of his best known compositions.

Falla was born in the Andulusian city of Cadiz, the same place that Columbus launched his fateful voyage from in 1492. His first important work was the one-act opera La vida breve (or Life is Short), written in 1905 while Falla was living in Madrid. The other piece on the program, El Amor Brujo, is among Falla’s most celebrated works. Originally scored for chamber orchestra, then a symphonic piece, it eventually became a ballet in 1925. Strongly informed by flamenco, the ballet tells the ghostly story of a woman’s haunting by the spirit of her unfaithful dead husband, finally banished during the Ritual Fire Dance.

Falla moved to Argentina in 1939 following the victory of Franco’s Fascist regime in the Spanish Civil War, never to return home. He died in 1946.

Manuel de Falla’s website. has a detailed chronology of his life and complete list of his works in both English and Spanish.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

The video is filmmaker Carlos Saura’s hypnotic interpretation of the Ritual Fire Dance from his film of El Amor Brujo.

[/one_half_last]

[one_half]

Silvestre Revueltas

La Noche de los Mayas

In the liner notes accompanying in a recording of two of his works by the Santa Barbara Symphony conducted by Gisele Ben-Dor, there’s a great line about Silvestre Revueltas’ relationship to Mexican music and culture: “His film score to La Noche de los Mayas sounds like Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring on mescal. His Homenaje a Garcia Lorca has the body of a chamber work and the soul of a mariachi.”

In the liner notes accompanying in a recording of two of his works by the Santa Barbara Symphony conducted by Gisele Ben-Dor, there’s a great line about Silvestre Revueltas’ relationship to Mexican music and culture: “His film score to La Noche de los Mayas sounds like Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring on mescal. His Homenaje a Garcia Lorca has the body of a chamber work and the soul of a mariachi.”

Revueltas was born at the very dawn of the 20th century and spent his teenage years caught up in the Mexican Revolution. He began his formal musical studies at National Conservatory in Mexico City, St. Edward’s University in Austin, Texas, and, coincidentally, the Chicago Musical College, which later became part of Roosevelt University. In 1929 he was invited by Carlos Chávez to become assistant conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra of Mexico, a post he held until 1935. Tragically, Revueltas died just 5 years later after struggles with poverty and alcoholism.

La Noche de los Mayas is a 1939 Mexican film that is described as a tragedy that takes place during the time of Mayan civilization. Revueltas composed the score. It was later made into a suite, and our Dia de los Muertos concert features an arrangement by the conductor, Gisele Ben-Dor.

The complete liner notes to the Santa Barbara Symphony recording are here.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

The video has music from the work’s final movement accompanied by dramatic images of Mayan temples and pyramids.

[/one_half_last]

[one_half]

Astor Piazzolla

Adios Nonino

Astor Piazzolla was born in Mar del Plata, Argentina to Italian immigrants. For many years Piazzolla lived something of a double life, playing in tango bands by night, studying classical composition by day. While studying in Paris with Nadia Boulanger, he was made aware that the ‘classical’ forms he was copying did not reflect his true soul. Returning to Buenos Aires, Piazzolla formed his first of several tango bands and began creating wild and bold innovations to the traditional and conservative form. Known as Tango Nuevo, he incorporated elements of jazz and classical music, expanding the harmonic and rhythmic vocabulary of the style.

Astor Piazzolla was born in Mar del Plata, Argentina to Italian immigrants. For many years Piazzolla lived something of a double life, playing in tango bands by night, studying classical composition by day. While studying in Paris with Nadia Boulanger, he was made aware that the ‘classical’ forms he was copying did not reflect his true soul. Returning to Buenos Aires, Piazzolla formed his first of several tango bands and began creating wild and bold innovations to the traditional and conservative form. Known as Tango Nuevo, he incorporated elements of jazz and classical music, expanding the harmonic and rhythmic vocabulary of the style.

His radical innovations were met with a great deal of controversy, including having his life threatened during an interview at a radio station by a drunken tango singer wielding a gun. In fact, there were several brushes with death because of his work. Adios Nonino, was composed to honor his father upon his death in 1959.

Piazzolla.org has a wealth of information on the composer and about Tango Nuevo.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

In this video, Piazzola himself accompanies the Cologne Radio Orchestra on Adios Nonino.

[/one_half_last]

[one_half]

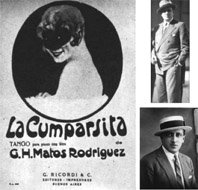

Gerardo Matos Rodriguez arr. Raul Jaurena

La Cumparsita

La Cumparsita is generally regarded as tango’s most famous song. Uruguayan musician Gerardo Matos Rodriguez wrote the initial melody in 1916. In actuality, it is three songs that were put together by band leader Roberto Firpo: Matos Rodriguez’s La Cumparsita (a carnival march) plus parts of Firpo’s tangos La Gaucha Manuela and Curda Completa. It was promptly recorded and released as the ‘B’ side of another song. After a modest run, it faded and might have stayed that way had it not had lyrics added in 1924 and recorded by the great tango singer Carlos Gardel. The title was changed as well, to Si Supieras. This is the version that earned widespread fame, so much so that Matos Rodriguez, now living in Paris, heard it and promptly sued for royalties. After two decades in court, the issue was settled. The name La Cumparsita was restored along with 80% ownership to Matos Rodriguez.

La Cumparsita is generally regarded as tango’s most famous song. Uruguayan musician Gerardo Matos Rodriguez wrote the initial melody in 1916. In actuality, it is three songs that were put together by band leader Roberto Firpo: Matos Rodriguez’s La Cumparsita (a carnival march) plus parts of Firpo’s tangos La Gaucha Manuela and Curda Completa. It was promptly recorded and released as the ‘B’ side of another song. After a modest run, it faded and might have stayed that way had it not had lyrics added in 1924 and recorded by the great tango singer Carlos Gardel. The title was changed as well, to Si Supieras. This is the version that earned widespread fame, so much so that Matos Rodriguez, now living in Paris, heard it and promptly sued for royalties. After two decades in court, the issue was settled. The name La Cumparsita was restored along with 80% ownership to Matos Rodriguez.

In 1997, the government of Uruguay declared La Cumparsita the official Culture and Popular Anthem of the country.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

The video plays a classic 1940 recording of La Cumparsita set to vintage images of Montevideo and tango dancers.

[/one_half_last]

[one_half]

Luis Enríquez Bacalov

Theme from Il Postino (The Postman)

Il Postino is a film that tells the fictionalized story of exiled Chilean poet Pablo Neruda’s time in Italy and his friendship with the man who delivers his mail. Who better, than, to write the score than Luis Enríquez Bacalov, the Buenos Aires born composer who has lived in Italy since the 1950s. The highly prolific Bacalov began his career writing scores for Spaghetti Westerns and, in the 1970s, collaborated with various Italian progressive rock bands. Quentin Tarantino used two songs from his 1960s era film music in Kill Bill. He has had two film scores nominated for Academy Awards. His music for Il Postino won in 1996.

Il Postino is a film that tells the fictionalized story of exiled Chilean poet Pablo Neruda’s time in Italy and his friendship with the man who delivers his mail. Who better, than, to write the score than Luis Enríquez Bacalov, the Buenos Aires born composer who has lived in Italy since the 1950s. The highly prolific Bacalov began his career writing scores for Spaghetti Westerns and, in the 1970s, collaborated with various Italian progressive rock bands. Quentin Tarantino used two songs from his 1960s era film music in Kill Bill. He has had two film scores nominated for Academy Awards. His music for Il Postino won in 1996.

Recent years have found Bacalov expanding into larger works for chorus and orchestra, including Misa Tango, an adaption of the liturgy to Argentine forms, Cantones de Nuestro Tiempos, and a triple-concerto for bandoneón, piano, soprano and symphony orchestra.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

In this video, Il Postino is presented in recital with Bacalov himself on piano.

[/one_half_last]

[one_half]

Maurice Ravel

Pavane pour une infante défunte (Pavane for a Dead Princess)

French composer Maurice Ravel might seem to be an odd choice for a concert that focuses on Spanish and Latino composers, but consider this: Pavane pour une infante déunte is not, as you might expect, a mournful remembrance but, in Ravel’s words, “an evocation of a pavane that a little princess might, in former times, have danced at the Spanish court”. Those former times are the 16th and 17th centuries, making the pavane a dance popular a full 300 years before Ravel wrote it, and it expresses a nostalgic enthusiasm for Spanish customs and sensibilities. It’s also worth noting that Ravel’s most popular work bears a Spanish name: Boléro.

French composer Maurice Ravel might seem to be an odd choice for a concert that focuses on Spanish and Latino composers, but consider this: Pavane pour une infante déunte is not, as you might expect, a mournful remembrance but, in Ravel’s words, “an evocation of a pavane that a little princess might, in former times, have danced at the Spanish court”. Those former times are the 16th and 17th centuries, making the pavane a dance popular a full 300 years before Ravel wrote it, and it expresses a nostalgic enthusiasm for Spanish customs and sensibilities. It’s also worth noting that Ravel’s most popular work bears a Spanish name: Boléro.

Ravel originally wrote the pavane as a solo piano piece at the age of 24. It achieved popularity after Spanish pianist Ricardo Viñes performed it in 1902. In 1910, Ravel orchestrated it with the trumpet carrying much of the melody, and that is the version played at this concert. Upon its premiere, it was declared by one critic “most beautiful”, praising its “subdued expression, and a somewhat remote beauty of melody.”

The Maurice Ravel Frontispice contains a list of his compositions along with biographical information and a somewhat offbeat approach including dozens of quotes about and by the composer.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

The video features Cuban jazz trumpeter Arturo Sandoval’s recent interpretation.

[/one_half_last]

[one_half]

Arturo Márquez

Danzon No. 4

Our concert fittingly concludes with three works from Mexican composers. Arturo Márquez is the first of these. Like others on the program, Márquez plumbed the traditions of Mexican music to compose his orchestral works. In fact, his Danzón No. 2 is sometimes considered, along with José Pablo Moncayo’s Huapango, an “unofficial” national anthem of Mexico. Unlike Galindo and Moncayo, Márquez is very much alive and creating new music i the 21st century.

Our concert fittingly concludes with three works from Mexican composers. Arturo Márquez is the first of these. Like others on the program, Márquez plumbed the traditions of Mexican music to compose his orchestral works. In fact, his Danzón No. 2 is sometimes considered, along with José Pablo Moncayo’s Huapango, an “unofficial” national anthem of Mexico. Unlike Galindo and Moncayo, Márquez is very much alive and creating new music i the 21st century.

Márquez’s father was a mariachi musician in Mexico and later in Los Angeles and his paternal grandfather was a Mexican folk musician in the northern states of Sonora and Chihuahua. He was exposed to several musical styles in his childhood, particularly Mexican “salon music” which would be the impetus for his later musical repertoire. His series Danzones were written in the 1990s, inspired by music from Veracruz and its direct relationship to Cuba. Danzon No. 4, while less known than No. 2, shares much of the clave rooted rhythm, sway, and instrumentation.

More on Márquez can he found here.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

The video features a recording of No. 4 led by Benjamín Juárez Echenique, a Mexico City born conductor who is currently Dean of the Boston University College of Fine Arts.

[/one_half_last]

[one_half]

Blas Galindo

Poema de Neruda

Mexican composer Blas Galindo was a contemporary and friend of José Pablo Moncayo. Like Silvestre Revueltas, he was influenced by Carlos Chavez, under whom he studied and was later named Director of the National Conservatory of Music. Unlike Revueltas, though, Galindo lived a long and successful life, continuing to write new music well past the age of 70. Like Moncayo and a few other composers of the time, he sought to use indigenous Mexican musical materials in art-music compositions.

Mexican composer Blas Galindo was a contemporary and friend of José Pablo Moncayo. Like Silvestre Revueltas, he was influenced by Carlos Chavez, under whom he studied and was later named Director of the National Conservatory of Music. Unlike Revueltas, though, Galindo lived a long and successful life, continuing to write new music well past the age of 70. Like Moncayo and a few other composers of the time, he sought to use indigenous Mexican musical materials in art-music compositions.

Here is where the poet Pablo Neruda enters the picture again. It’s impossible to overstate the importance of Neruda to Latin American arts and culture. Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez once called him “the greatest poet of the 20th century in any language” and in 1971 Neruda won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Galindo’s Poema de Neruda is written for string orchestra and at times its elegiac feel calls to mind Barber’s Adagio. It’s not certain which, if any, poem inspired the work, but from the sound of it, it could have easily been from Neruda’s 1924 collection Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair.

More on Galindo is here, and Neruda’s Wikipedia page also has an extensive biography.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

The video is of the Orquesta Filarmónica de Jalisco performing the piece in February 2010 under the baton of Maestro Hector Guzman.

[/one_half_last]

[one_half]

José Pablo Moncayo

Sinfonieta

Our concert concludes with a piece from a composer who has already been referenced twice in this guide: José Pablo Moncayo. That should tell you something about his stature among Mexican composers and with the Mexican people. His lively Huapango, modeled after the traditional folk dances of Veracruz, is one of the best known Mexican orchestral pieces of all time. Moncayo was a pianist, percussionist, music teacher, composer and conductor who, like his friend Blas Galindo and Silvestre Revueltas, was championed by Carlos Chávez. Like the other two, he was inspired by the ideals of the Mexican revolution.

Our concert concludes with a piece from a composer who has already been referenced twice in this guide: José Pablo Moncayo. That should tell you something about his stature among Mexican composers and with the Mexican people. His lively Huapango, modeled after the traditional folk dances of Veracruz, is one of the best known Mexican orchestral pieces of all time. Moncayo was a pianist, percussionist, music teacher, composer and conductor who, like his friend Blas Galindo and Silvestre Revueltas, was championed by Carlos Chávez. Like the other two, he was inspired by the ideals of the Mexican revolution.

Sinfonieta, written 4 years after Huapango, was premiered by Orquesta Sinfónica de México conducted by the composer. It, too, is a rhythmic and celebratory work. Though not as obviously modeled after traditional folk music, it feels a bit like Aaron Copland’s western inspired work while retaining a distinctly Mexican character.

Moncayo’s Wikipedia entry is thorough in its research.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

To get some sense of the folk music that inspired Moncayo, check out this informal video of Huapango with Mexican traditional ensemble Sones de Mexico accompanied by Chicago Sinfonietta Chamber Ensemble in a 2008 performance at the National Museum of Mexican Art.

[/one_half_last]